Twin Cities, Minnesota

Project: A Damning Deluge: The Rhetoric of Damming the Mississippi Headwaters Region and Ojibwe Resistance to Environmental Injustice

Chris Rico

In the 1880s, the U.S. Government funded the construction of two dams in north-central Minnesota at Lake Winnibigoshish and Leech Lake—the start of a decades long series of damming projects spanning the Headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota.[1] This essay focuses on two such dams, which displaced thousands of community members from the Pillager, Winnibigoshish, Mississippi, and Leech Lake bands of Ojibwe who were living in the area at the Leech Lake and Winnibigoshish reservations. Before the project was to begin, a commission was tasked by the federal government to assess damages to the Ojibwe communities who would be displaced—the project was not to move forward until an agreement was reached between the commission and Ojibwe communities on fair compensation. The commission found that 46,920 acres of land were to be affected for which it concluded that $15,466.90 would constitute just compensation.[2] However, Ojibwe community leaders stated that $250,000 to be paid indefinitely every six months would constitute just compensation.[3] The commission refused to meet the latter number and construction began as soon as the former was calculated.

Ojibwe communities refused to agree to the number made up by the commission and resisted the government’s attempts to justify it as fair compensation by forcing commission leaders to see the lands’ worth through their eyes and to face the injustice the number represented. I will highlight how Ojibwe communities resisted the projects and outright refused the government’s idea of damage payments through their own words. Furthermore, I seek to position the commission and government’s thinking within a lens of industrial capitalism and environmental injustice while centering Ojibwe resistance to these modes of settler colonialism.

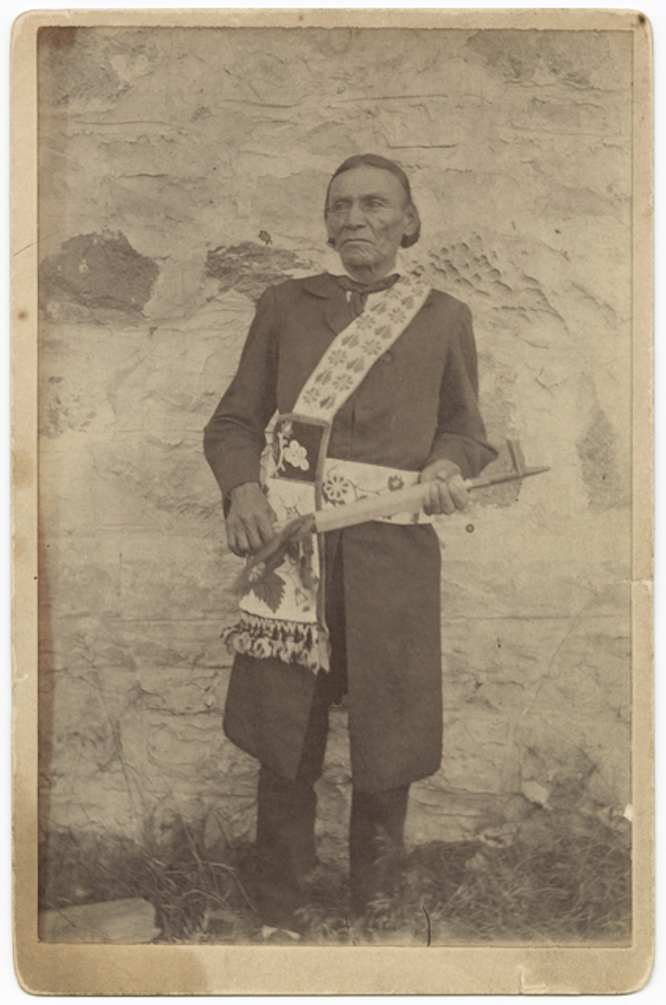

“He says we are to be paid a cent an acre. As poor as I am, if forced to take this money, I would take it and throw it away.”[4] These words, written by Chief Wa-bon-a-quot (White Cloud) of the Mississippi bands of Ojibwe, speak to the resolve of these communities in refusing to accept anything less than what they knew their lands to be worth. It was well known by all that the rising water levels created by the dams would severely disrupt if not completely impede the ability of Ojibwe living in the area to sustain themselves, not to mention the disruption it would cause to their lifeways.[5] In speaking to this disruption and the comparatively small compensation, Chief Ne-gaun-e-be-nace (Flat Mouth) of the Pillager band of Ojibwe, said that “[w]e don’t wish this; as this is our property we will not accept a small price […] No one that comes here and stops for a while can know how important this is to us […] if these dams are made we will all be destroyed.”[6] Ojibwe communities went on to refuse the dams and forced commission leaders to negotiate on their terms. However, the commission did not see the lands with the same eyes as the communities who lived there.

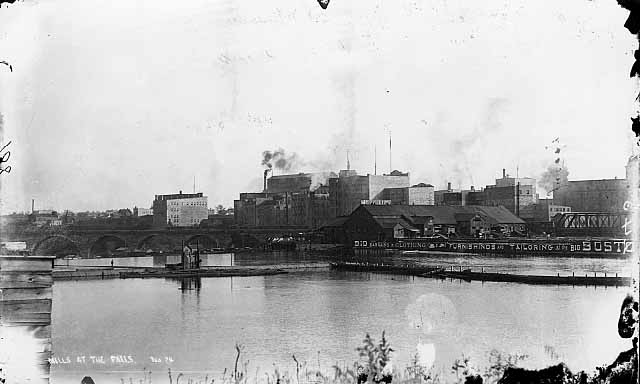

In the mid-19th century, flour milling, logging, and river transportation were growing industries in Minneapolis. All held in common a reliance on the Mississippi River and a desire for better control and predictability of the flow of the river for the success and growth of their operations. These desires were met in part by the federal River and Harbor Acts of June 14, 1880 and March 3, 1881 which funded the construction of the dams at Lake Winnibigoshish and Leech Lake.[7]

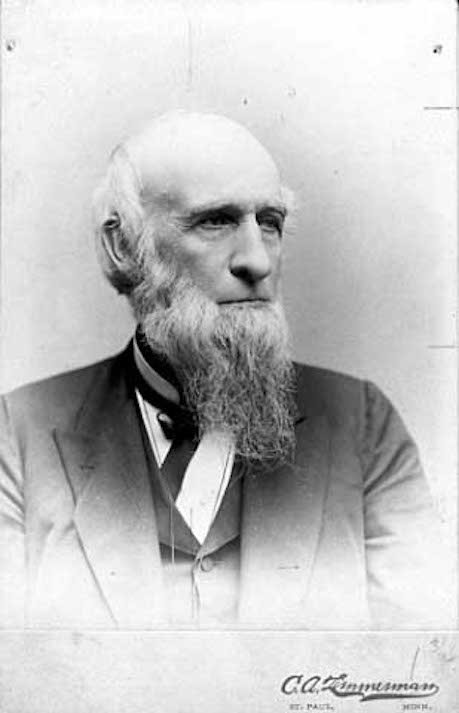

In the eyes of the settler state and industrial capitalists, the damming, and any adverse effects it might have on communities in the path of the rising waters, could be justified due to their ideas about the “usefulness” of the affected land. Indeed, Captain Russell Blakeley, Chairman of the commission to assess the damages of the dams characterized much of the land to be affected as “poor tamarack swamp.”[8] Blakeley emphasized the presence of swamp lands in the area to create what Dr. Traci Brynne Voyles calls “sacrifice zones.” In her book, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, Voyles characterizes wastelanding as a spatial and racial process used by the settler state to justify the destruction of lands most often held by non-white communities.[9] Wastelanding made the choice to displace Ojibwe communities by flooding important ecological resources and reservation land in order to improve industry in Minneapolis an easy one for the government and industrial capitalists.

The Ojibwe communities affected by the dams were not and are not helpless. They demonstrate their agency and tribal sovereignty by their actions within this power imbalance. In refusing to accept the commission’s idea of fair compensation, they forced the government to negotiate on their terms and attempted to reach a consensus on the land’s worth as it was to those living there. Additionally, the government would have to reckon with the injustice they committed to these communities. Nearly one hundred years later, Ojibwe communities are still refusing to let the matter go. In 1985, in an out-of-court settlement with the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, the federal government agreed to compensate communities affected by these and other historical damming projects around the Headwaters region for 178,000 acres of reservation land, and 5% accumulated interest starting from 1884 which amounted to $3,390,288.[10]

Today in Minnesota, Ojibwe communities continue to resist environmental injustices produced by industrial capitalism. In north-central Minnesota, the Canadian Oil company Enbridge is currently constructing the Line 3 pipeline which threatens millions of acres of wetlands, waterways, and wild rice stands guaranteed by treaty and depended upon by Ojibwe communities for spiritual health and subsistence. While the pipeline is touted as a safe method of transporting oil, “sacrifice zones” are inherently created through the pipeline’s path. It is never a matter of if pipelines will rupture, but when and how much.[11] However, as with resistance to the dams, indigenous-led organizations like Honor the Earth and the GINIW Collective refuse to accept the construction of the pipeline and the wastelanding of their homes and sacred lifeways. At every opportunity, these organizations and local community members are organizing resistance to the pipeline through protest and court action.[12]

Author Note: The author of this essay would like to identify himself as a non-indigenous, white settler scholar and Indigenous ally. The lands which he and those like him occupy have never belonged to him but have instead come through a legacy of genocide, internment, and removal of indigenous communities. Specifically, the lands today known as Minnesota are the traditional and current homelands of the Dakota and Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) peoples. By researching issues like those discussed in this essay, he hopes to spread awareness of these injustices amongst himself and others of settler descendancy. He also recognizes that awareness of these issues is only the first step towards justice and does not constitute justice itself. He encourages those of settler descendancy who can, to research and participate in land back initiatives, acts of solidarity, mutual aid, and other avenues of actionable support and change for Indigenous communities in their area. He would also like to thank Dr. Jean O’Brien, Dr. Michael Dockry, and Dr. Kevin Murphy for reviewing this essay and supporting him throughout his experience with this and other works.

Notes

[1] The entire system resulting from this project is a series of 6 dams, this essay focuses on only the first two erected. For a more complete history of the damming projects see: https://www.mnopedia.org/thing/mississippi-river-reservoir-dam-system

[2] U.S. House of Representatives, Damages to Chippewa Indians, Exec. Doc. No. 76, 48th Cong., 1st Sess. (Washington, DC: GPO, 1884), 1-3

[3] Ibid., 26, 28-29, 33.

[4] U.S. House of Representatives, Damages to Chippewa Indians, 8.

[5] David R. Treuer, “The Rhetoric of Reservoirs,” Minnesota History, Vol 53, no. 4 (Winter, 1992): 158. See also: Jane Lamm Carrol, “Dams and Damages: The Ojibway, the United States, and the Mississippi Headwaters Reservoirs,” Minnesota History, Vol. 52, no. 1 (Spring, 1990): 10.

[6] U.S. House of Representatives, Damages to Chippewa Indians, 29

[7] Forty-Sixth Congress, Sess. II. Ch. 211 (Washington DC: GPO, 1880), 193. See Also: Forty-Sixth Congress, Sess. III. Ch. 136 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1881), 481.

[8] U.S. House of Representatives, Damages to Chippewa Indians, 27.

[9] Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 9-10.

[10] Jane Lamm Carrol, “Dams and Damages,” 3, 14.

[11] From 1996 to 2014 Enbridge alone has recorded 1,276 pipeline ruptures equating to 9,423,708 gallons of spilled oil. See: https://world.350.org/kishwaukee/files/2017/02/EnbridgeMajorSpills_1996-2014.pdf

[12] To see how the GINIW Collective has been resisting Line 3 construction, visit their Facebook page at: https://www.facebook.com/giniwcollective; To see how Honor the Earth is resisting Line 3 visit their webpage at: https://www.honorearth.org/; In the last several years Ojibwe and Indigenous governmental organizations have also taken legal steps to protect their lands and relatives therein, see the Rights of Manoomin legal document drafted by the White Earth band of Ojibwe which recognizes wild rice’s rights as a living being: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1J44ImxMHtGYWmsdRpTDNiiUFEK0fWCXd/view; Finally, see the National Congress of American Indians’ resolution on pollutants from sulfide mining in Northern Minnesota: https://www.ncai.org/resources/resolutions/protecting-chippewa-lands-and-resources-from-the-threats-posed-by-polymet-mine