Los Angeles and the Inland Empire, CA

Project: From Rose Colored Nostalgia to Seeing Red: Kaiser Steel and the Slow Violence of the Supply Chain

Alyse Yeargan

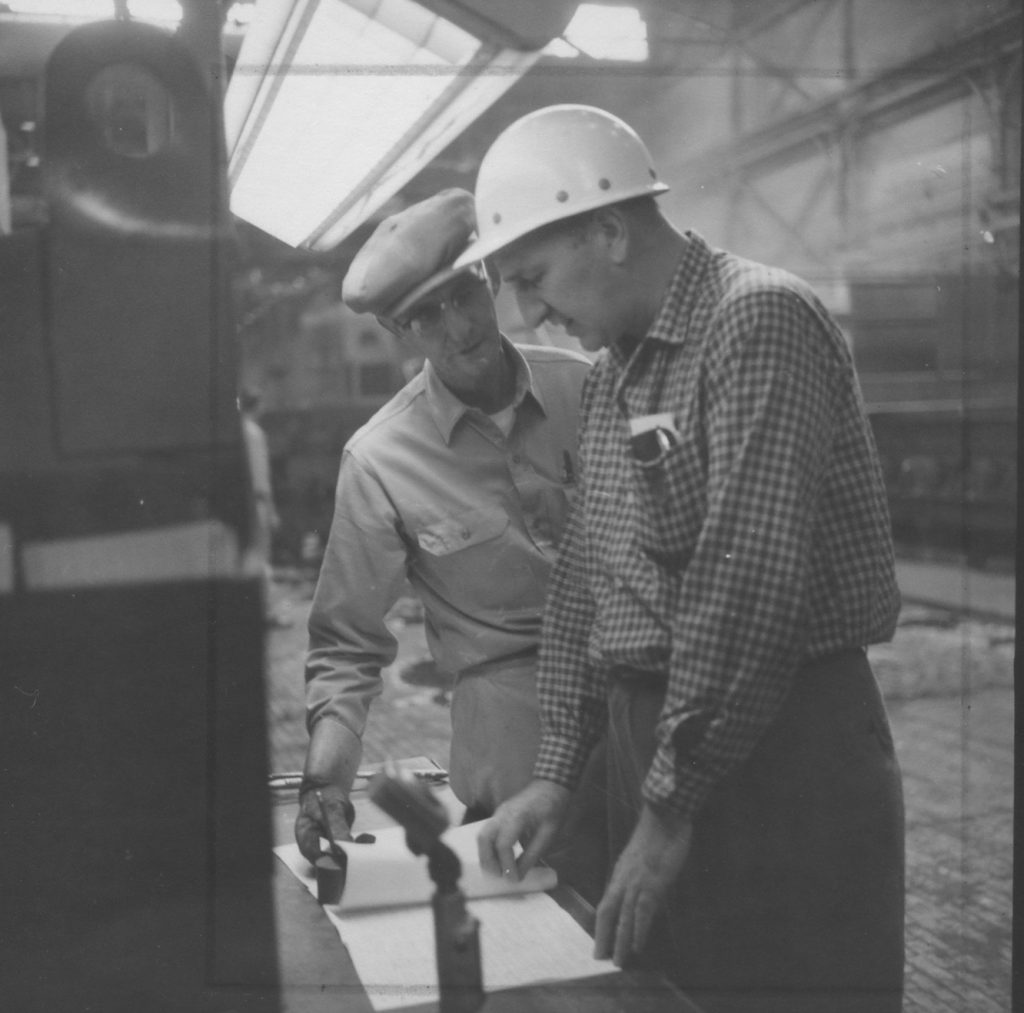

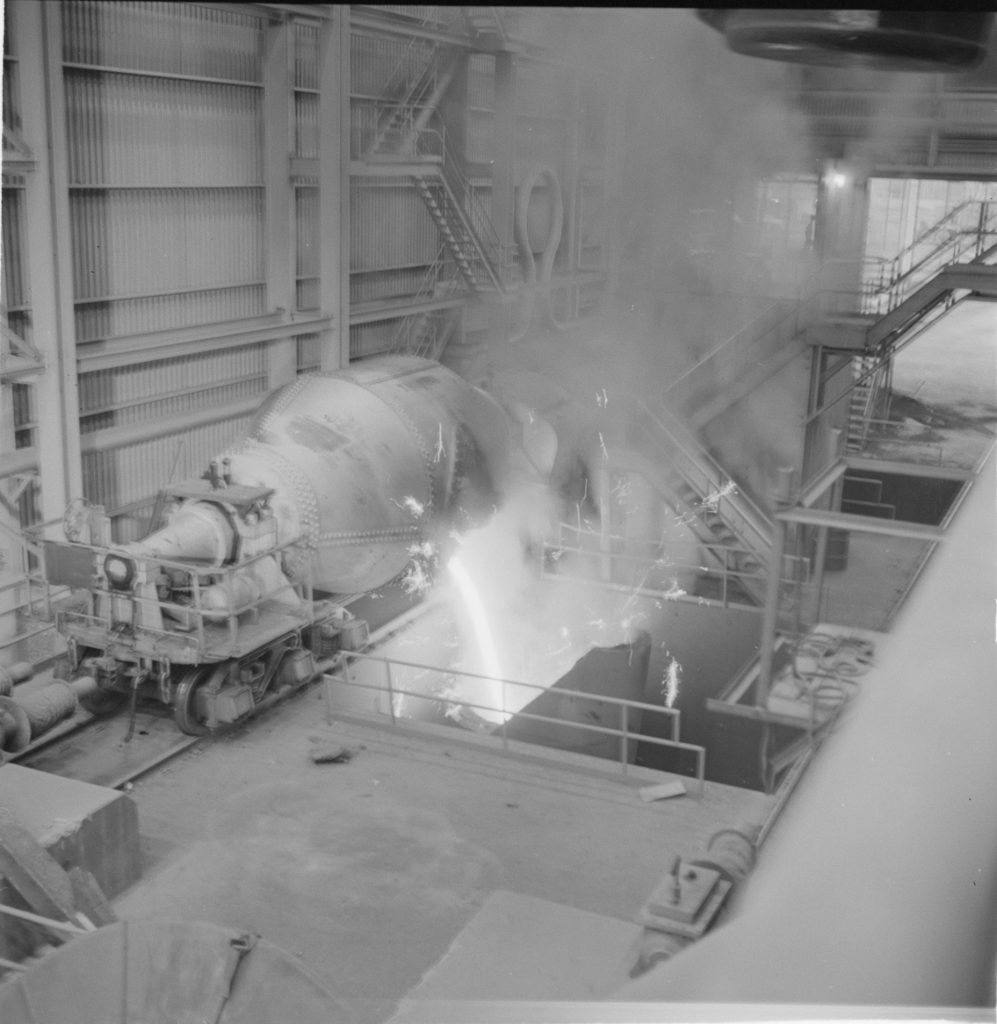

In 1958, LA-based industrial photographer Will Connell was commissioned by Kaiser Steel in Fontana, California, to document for promotional purposes the expansion of the 50,000-square-foot mill. His images occupy a central place in the mythologizing of mid-century industrial labor and the landscape of Southern California’s Inland Empire. Contemporary generations often look back to the era as one of jobs and relative prosperity. Connell ennobles the laboring past that many from the area also see through rose-colored glasses, as they remember when union jobs brought bread to an upwardly mobile middle-class table. After employing more than 100,000 from 1942 to 1983, Kaiser closed, its parts sold to China, and its pitted landscape left behind along with the other scars of deindustrialization.

The rosy view of industrial unionized labor, like that provided for Fontana by Kaiser Steel Mill, and the purposefully valorizing images of men at work like those created by Connell hide the insidious environmental and physiological effects of this work. (1) Scholar Rob Nixon describes this type of damage as slow violence; it “is neither spectacular nor instantaneous but instead incremental, whose calamitous repercussions are postponed for years or decades or centuries.” (2) It occurs so incrementally as to be rendered nearly invisible to the casual observer or outsider. (3) The damage done in Fontana is historically ongoing, and has an impact not only on the environment but also on the human labor force. The slow violence experienced both by the land and people of Fontana is not often remembered today in terms of a not-so-distant trajectory. Rather, as community members grapple with contemporary challenges of industrial development, precarious jobs, and environmental degradations arising from the logistics industry, they often paint a rosy picture of the union jobs at places like Kaiser, forgetting the public and environmental health costs and limitations faced by non-whites working at the plant. As city leaders have accommodated global corporations on their recent quest for land to facilitate the distribution of goods from coastal ports to the inland region, without questioning the promise of providing much-needed jobs, a mythical past has been constructed. This includes a labor (and environmental) narrative of sudden ruination that is belied by on-the-ground history.

In fact, the area has a long history of exploitation. It was once home to Fontana Farms–“one of the largest agricultural operations in North America,” which ran “at least partly on the backs of young” Native American “men from Sherman Institute.”(4) In the years “between 1908 and 1929, at least 347 male students from Sherman Institute lived and worked at the Fontana Farms Company.” (5) This labor was deeply exploitative; workers struggled not only against systemic racism against Native Americans, but also had to negotiate “dangerous working conditions, suffered subpar housing, and struggled to communicate with fellow workers across linguistic and cultural barriers.” (6)

Agricultural industries began to decline in the 1940s and Fontana Farms was replaced by the Kaiser Steel Mill in 1942. The farm–and its 50,000 pigs–were often used as a clever motif in Kaiser publications, wherein workers were often cartoonishly illustrated as pigs doing steel mill jobs. (7) The lasting impression of these illustrations is less flattering, suggesting Kaiser Steel saw their workers as expendable meat. Kaiser Steel’s opening in 1942 coincided with the opening of Norton and March Air Bases, as well as nearby Mira Loma Substation–a U.S. Army Quartermaster’s facility for providing logistical support, sending supplies to Manzanar in the early years of Japanese incarceration, desert training camps, and in the 1950s to Korea. It rapidly became part of a logistics network of its own–one that supplied the war efforts for World War II and the Korean War. (8)

The plant has been praised by scholars, community members, and former workers, particularly those in the Latinx and immigrant communities who made up the majority of the workforce, as positive and receptive to labor reforms. Though the working conditions might have been heralded by some, Kaiser himself was frequently derided by competitors as a “socialist” because of his proactive reforms and receptiveness to union complaints. (9) This memory seems to be a bit tinted with nostalgia as well, and it was bolstered by photos of Kaiser steel like those by Will Connell whose photos are featured throughout this essay. (10) During and after the war, a surge in migration to the area was supported by jobs provided by the mill. However, Kaiser worked especially hard to attract “skilled white workers by providing a social safety net that included affordable healthcare and housing.” (11) He made no such efforts for his “multiracial blue-collar workforce,” though. (12) Many of “the worst jobs were reserved for African American and Latinx workers.” (13) Racial tension at the plant were exceptionally high and at times race riots were a genuine concern of the management.

In addition, the Kaiser mill also contributed heavily to pollution both in Fontana and at Eagle Mountain nearby, where the iron ore mine (supplying the plant) was located. Over “2.25 million tons of iron ore” were extracted from “an open-pit mine” at Eagle Mountain. (14) Organizers at the Ontario-based Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice have conducted interviews with former workers at the mine who now suffer from serious medical conditions such as emphysema resulting from steel mill labor. More recent generations, they note, similarly suffer from high rates of asthma and cancer linked to diesel pollution of truck traffic from the warehouses that now flank the old Kaiser mill and surrounding area. (15)

The environmental impacts of the logistics industry are currently being publicized and many community members in Fontana and adjacent neighborhoods are pushing back against the ways their communities have been exploited for industrial gains that don’t necessarily serve the community. Developers plan to build 3.4 million more square feet of warehouses, on an already logistics industry packed landscape–in Fontana alone (more are in the works for other parts of the I.E.). (16) While Fontana Mayor Warren and some other city council members insist that warehouses bring jobs to the area, others question the types and quality of the jobs they bring, which are frequently very poor. The site of these new warehouses, which were previously planned for homes, an elementary school, and recreation facilities, will now bring 6,000 jobs to the area–or so some claim. (17) Superficially, that sounds great. Only one third of the jobs will be permanent, however. (18) There is no word on the full or part-time status of those permanent positions, whether they will be paid well enough to provide a living wage or support families, and whether they will include benefits of any kind. (19) Many warehouse workers struggle to make anything near a living wage because none of these things are insured for them. (20) While warehouses do provide jobs, they are frequently poor in both compensation and in working conditions that can have negative impacts on workers’ health. (21) In the midst of these messages it is often tempting to think that labor conditions have suddenly become horrible– this is the trick which disguises slow violence.

Will Connell’s photos of men at work in the Kaiser Steel Mill created an innocuous vision of the labor offered by industrial production in the past. History can be useful in this case to prove that “blue-collar” work forces and particularly those including people of color have always faced unequal burdens, often poorly treated and placed in the most dangerous or toxic jobs. Currently, many are beginning to see redder than the molten iron Kaiser poured; organizations are protesting and looking for legal means of recourse to combat not just the slow but also the much quicker forms of violence they see in the confluence of environmental and labor degradations, in the name of the quickened supply chain. (22) If changes are to be made, they must entail creating new systems and protections for workers and the places where they live and circulate. We cannot simply hope to return to a mythical past.

——————————

1 Will Connell, a prominent industrial-commercial photographer in Southern California, was hired by Kaiser Steel to capture these images of the mill and men at work as promotional images, reproduced in annual reports and catalogs, among other uses. See Douglas McCullough, In the Sunshine of Neglect: Defining Photographs and Radical Experiments in inland Southern California, 1950 to the Present (Riverside: Inlandia Institute, and UCR Arts, 2018), 71.

2 Ashley Dawson, “Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor: An Interview with Rob Nixon,” Social Text, 31 August 2011. Accessed April 5, 2019. https://socialtextjournal.org/slow_violence_and_the_environmentalism_of_the_poor_an_interview_with_rob_nixon/.

3 Ibid

4 Kevin Whalen, Native Students at Work: American Indian Labor and Sherman Institute’s Outing Program, 1900-1945 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016), 58.

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 Juan D. De Lara, Inland Shift: Race, Space and Capital in Southern California (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2018), 118.

8 See video interview with Brinda Sarathy, “Mira Loma to Manzanar: The Roots of Logistics,” as part of Climates of Inequalities: Stories of Environmental Justice.

9 Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, new ed. (London ; Verso, 2006), 393; De Lara, 118; Center for Community and Environmental Justice (CCAEJ) presentation given at University of California Riverside April 22, 2019

10 De Lara, 118.

11 Ibid

12 Ibid., 119.

13 Ibid., 120.

14 Ibid., 117

15 CCAEJ presentation, April 22, 2019.

16 “Fontana approves plans to build seven warehouses in southeastern part of town,” Daily Bulletin http://www.sbsun.com/fontana-approves-plans-to-build-seven-warehouses-in-southeastern-part-of-town 2019-04-29.

17 Ibid. The numbers likely don’t take into consideration the rapid rate at which warehouses are automating, cutting scores of jobs in the process. Interview with Veronica Alvarado and Daisy Lopez, Warehouse Worker Resource Center, 30 May 2019.

18 Ibid.

19 Jake Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness, “Introduction: Forging Workers’ Resistance Across the Global Supply Chain,” in Choke Points: Logistics Workers Disrupting the Global Supply Chain, ed. Jake Alimahomed-Wilson and Immanuel Ness (Pluto Press, 2018), 3, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt21kk1v2.3; Ellen Reese and Jason Struna, “‘Work Hard, Make History’: Oppression and Resistance in Inland Southern California’s Warehouse and Distribution Industry,” in Choke Points, 83-85.

20 De Lara, 81.

21 Reese and Struna, “‘Work Hard, Make History,’” 83, 90.

22 Ibid., 82, 87.