Springfield, MA

Project: The Gerena School: Contested Grounds

Built in 1975 as an elementary school and community center in Springfield, Massachusetts’ North End, the German Gerena Community School was a “dream come true” to the diverse coalition of politicians, activists, and community members advocating for its construction since the mid-1960s. (1) Planners targeted the North End for construction of Interstate-91 in the 1960s, dividing the neighborhood in the process. Situated beneath I-91, Gerena attempted to heal urban renewal’s destruction by physically reconnecting the neighborhoods divided by the highway and providing community services. Unfortunately, Gerena’s low-lying location below I-91 and within the Connecticut River floodplain resulted in persistent environmental hazards that shuttered the school’s community services in 1994. The community center’s closure galvanized a coalition of neighborhood activists. Building on a long history of activism and political consciousness in the North End, they have applied pressure on civic and state authorities to alleviate the environmental hazards at Gerena and throughout the North End. Still, the community has yet to reach a consensus on the best course of action.

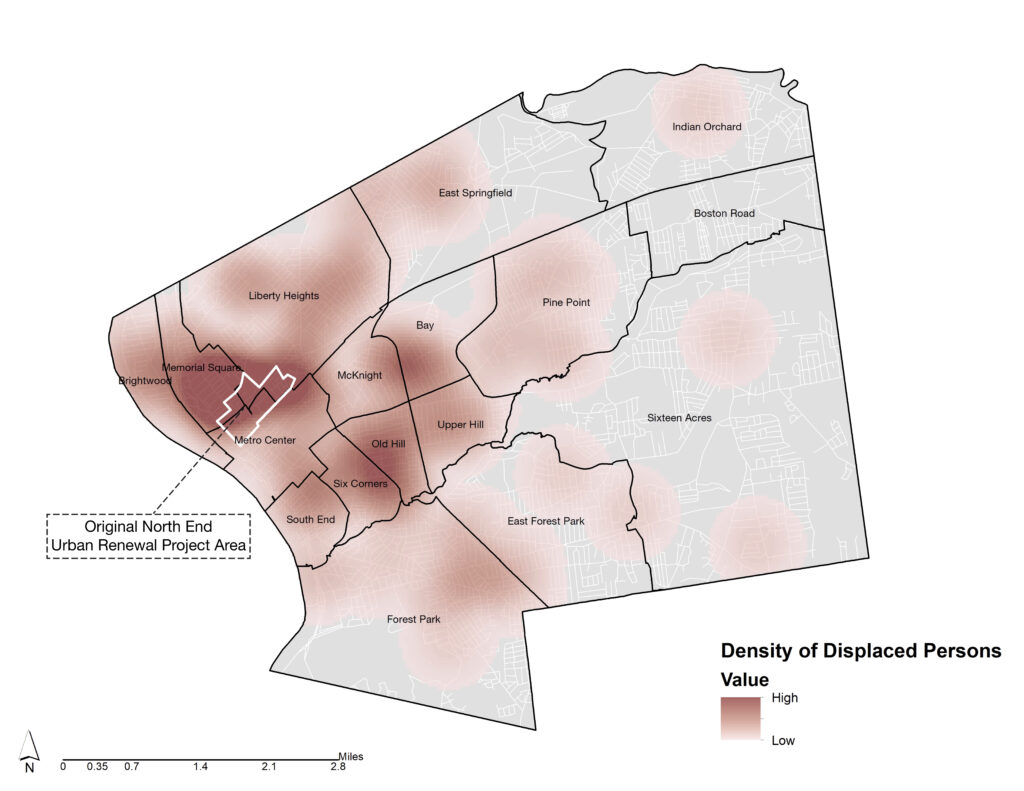

Urban renewal projects in Springfield exacerbated environmental problems in the North End by depleting the existing supply of affordable housing. Roughly sixty acres of homes and apartments that the city of Springfield deemed “blighted,” were leveled to make room for the interstate (Figure 1). Pushed from their homes and left with few other options, many displaced residents simply remained in the North End where housing stock was already strained beyond its capacity to provide a healthful environment (Figure 2). Urban renewal tied residents to these existing environmental injustices, but it created new respiratory health hazards as well. While

North End residents had experienced emissions from nearby heavy industrial and manufacturing firms for over a century, I-91 increased their exposure to emissions from the hundreds of thousands of cars that travel the highway daily. Most pressing to North End residents now and then was that I-91 divided the North End in half and limited neighborhood residents’ physical mobility.

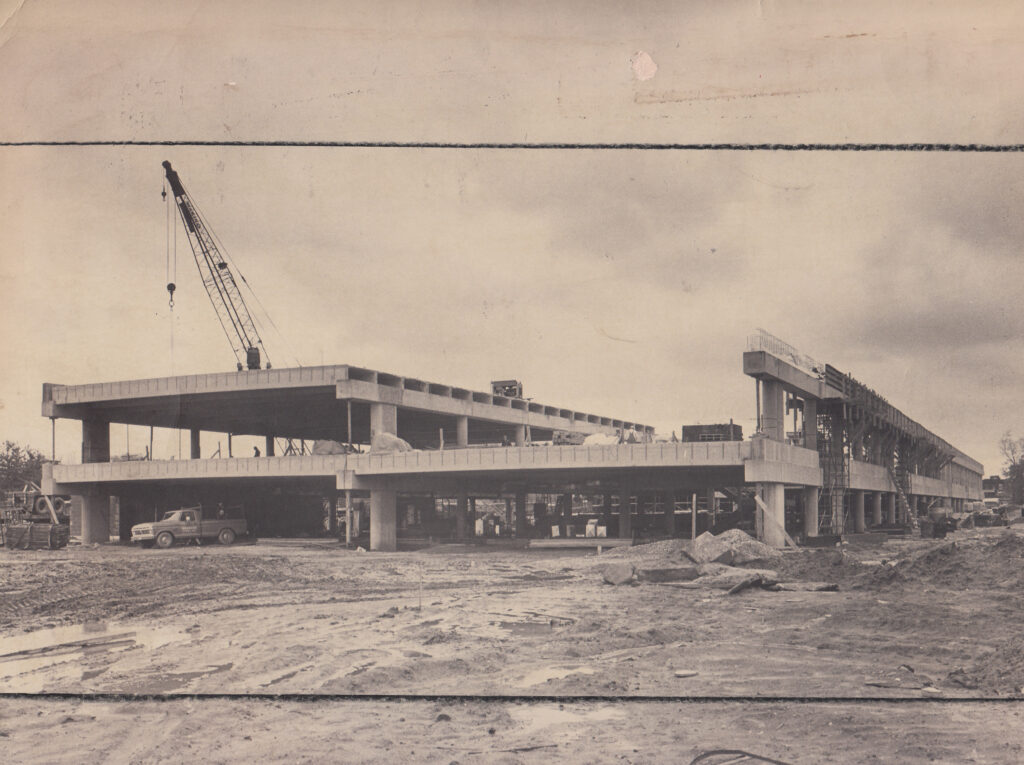

Gerena was conceived within broader efforts on the part of city planners carrying out urban renewal projects to alleviate the destruction wrought by those same projects (Figure 3). Yet these planners were also responding to a developing political consciousness from the North End’s growing Puerto Rican community. This loose coalition of neighborhood advocates argued for access to basic community services and programs, and articulated demands to help heal the physical destruction of their neighborhood. Gerena attempted to solve all of these problems identified by community activists and planners alike (Figure 4).

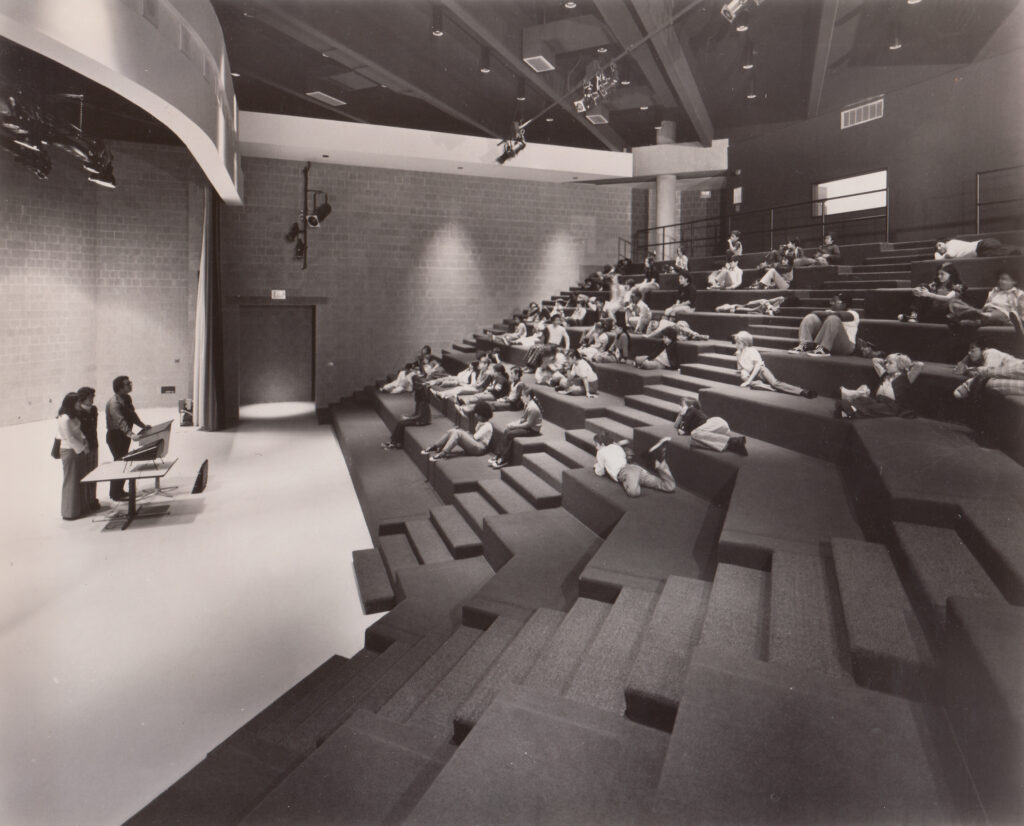

First opened as the New North Community School, Gerena physically reconnected the neighborhoods divided by the interstate by way of a tunnel beneath the school that functioned as a public community space (Figure 5). Within this tunnel level was a branch of the Springfield Public Library, a Puerto Rican community center, a health clinic, a division of the city’s parks and recreation office, a community music school, a senior citizens’ center, and spaces to facilitate adult and continuing education courses. To many North End residents, Gerena felt like “a family” at the center of their lives.

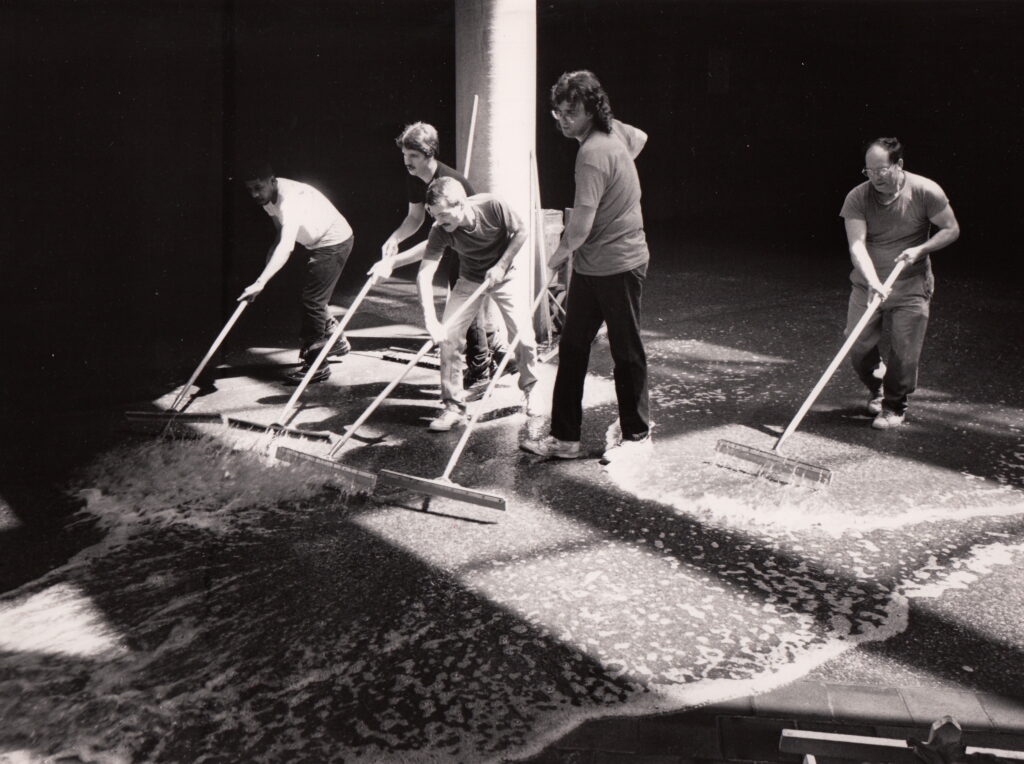

The Gerena School’s location made it susceptible to environmental hazards posed by I-91 and the Connecticut River floodplain. The school’s original, inadequately designed air handlers circulated the emissions from interstate traffic; in 1994, a broken water main flooded the tunnel

level of the school, forcing many of the services and programs residents relied on to relocate (Figure 6). The elementary school population Gerena served was bussed to other schools throughout Springfield while the city mitigated the flood’s damage (Figure 7). While the school children eventually returned to Gerena, the community services did not.

The 1994 flood posed a number of serious environmental hazards to those children still attending Gerena. The flood exacerbated mold in the tunnel, and contributed to a community-wide increase in respiratory health problems. North End residents, who are primarily Latinx, have an asthma rate twice as high as the Massachusetts state average. Already confined to unsanitary housing and exposed to the respiratory hazards of the interstate, the degradation around Gerena further galvanized North End activists (Figure 8).

A coalition of organizations, including the North End Citizens’ Council, Women on the Vanguard, and Neighbor to Neighbor, organized around these respiratory health problems. Many of these organizations drew from the neighborhood’s Puerto Rican activist roots to advocate for concrete solutions. This process of power mapping targeted city and state officials, whom activists believe have both the resources and authority to alleviate the environmental hazards at Gerena and throughout the North End. Their combined efforts initiated an Environmental Protection Agency Health Impact Assessment (HIA) report in 2014 that recommended repairs to promote positive health impacts at Gerena.

Since the release of the HIA, community activists have yet to reach a consensus on the best course of action. Some activists point to the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) as the authority responsible for alleviating the environmental issues of Gerena. As of May 2019, this political pressure has prompted the city of Springfield to seek reimbursement

from MassDOT to repair water leakage from the highway into the tunnel. Additionally, the city has requested funds from the Massachusetts State Building Authority to replace Gerena’s air handlers. Other activists point to City Hall, arguing that the city now has the financial resources, accrued through the construction of an MGM casino and marijuana dispensary, to thoroughly renovate and refurbish Gerena. Yet, as climate change increases rainfall throughout New England, making Gerena’s present location more vulnerable to flooding, some North End residents wish to see Gerena razed altogether and a new community center and elementary school built on higher ground. The memory of Gerena as a vital community asset persists in the minds of many longtime North End residents, however. For these North End residents, Gerena is contested grounds. But despite these different and sometimes competing strategies, community activists continue to situate Gerena within broader efforts to improve community-well being as they seek environmental justice (Figure 9).

———————————

1 New North Community School Committee, “New North Community School: Leads the way!” (Springfield, MA: New North Community School, 1981), 2.