Phoenix, AZ, and the Colorado River Basin

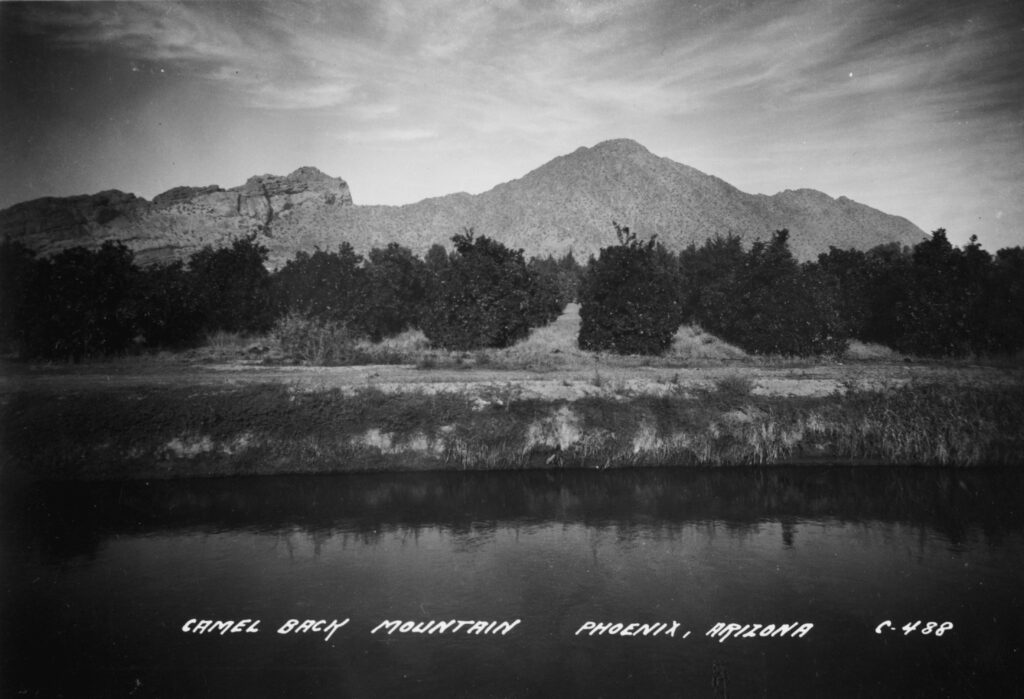

Completed in 1911, the Roosevelt Dam was constructed as a result of the 1902 National Reclamation Act.

Courtesy of Library of Congress.

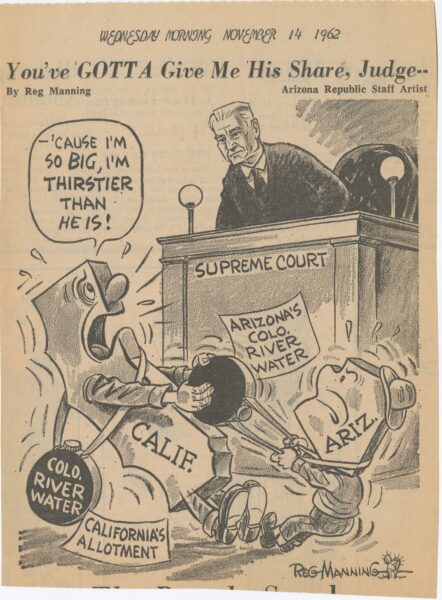

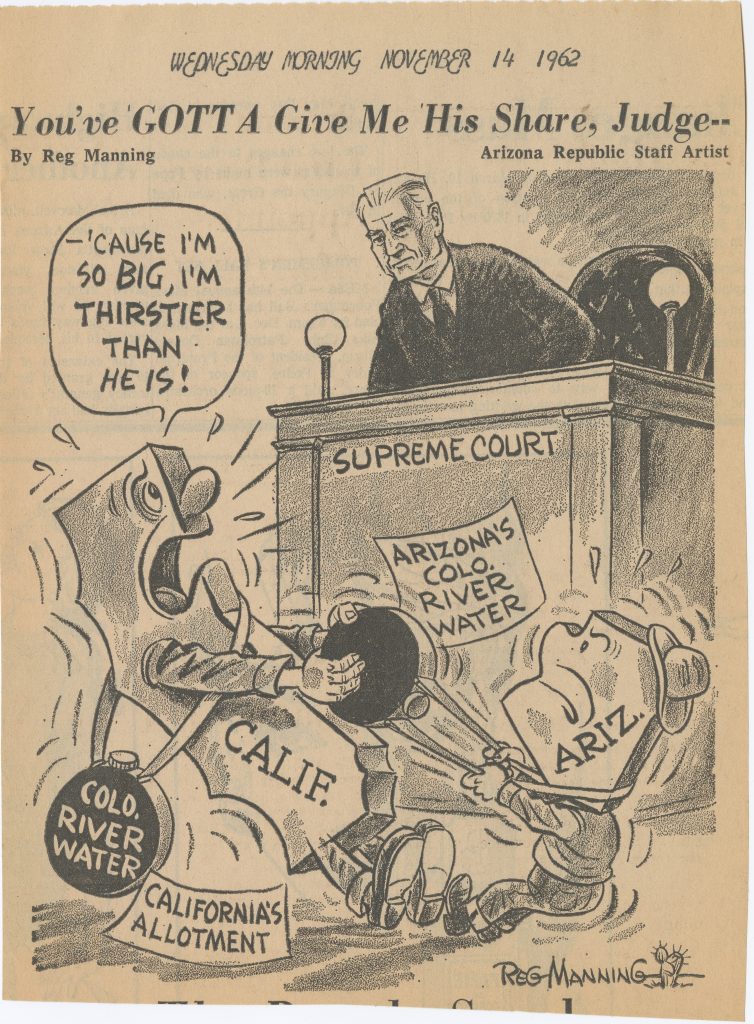

The Colorado River Watershed provides drinking water to 40 million people, irrigates 6 million acres, and supports countless ecosystems across the West. Climate change has reduced water supply; demand grows inexorably. There is no easy solution in sight.

Nineteenth-century Anglo migrants reengineered the Hohokam (300 to 1500 CE) canal system to settle central Arizona. Beginning in 1902, federal policies spurred the construction of a region-wide water infrastructure of dams and canals that encouraged further industrial and urban growth. By the last decades of the 20th century, the Central Arizona Project transported water from the Colorado River more than 336 miles from Lake Mead through Phoenix to Tucson, opening the way for new development that has stretched the region’s water supply beyond its capacity.

By creating dialogues that raise awareness of Arizona and the Colorado River Basin’s precarious water situation, we seek to encourage community resilience and help citizens to make informed and just choices about the allocation of water.