2018: Fishermen at Ciénaga de la Rinconada.

Courtesy of Diana Bocarejo.

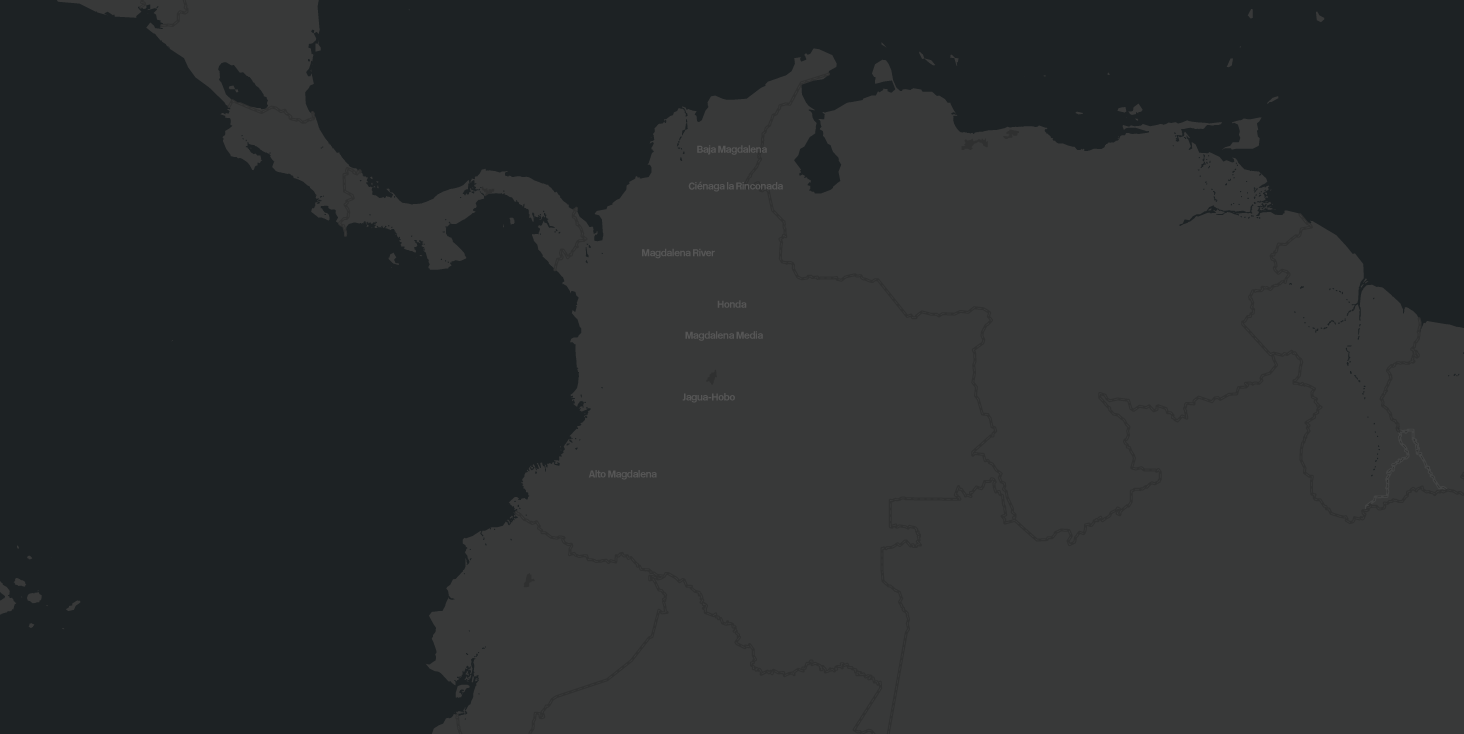

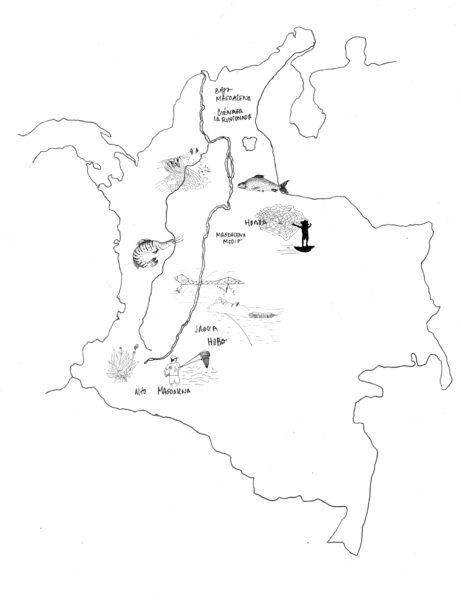

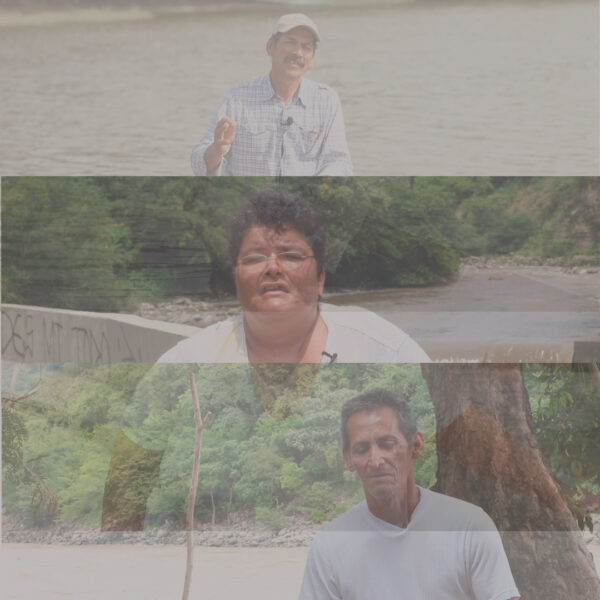

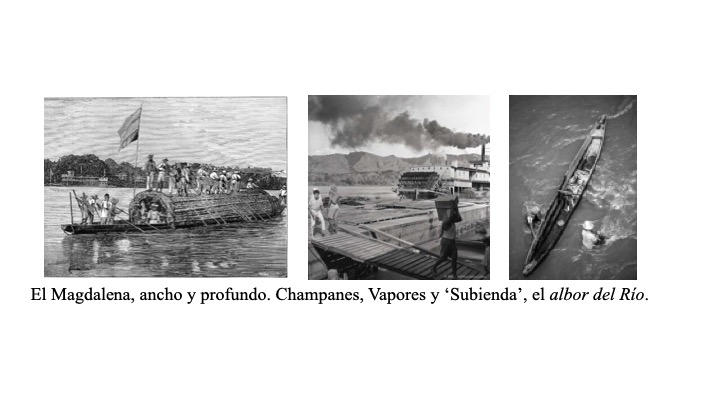

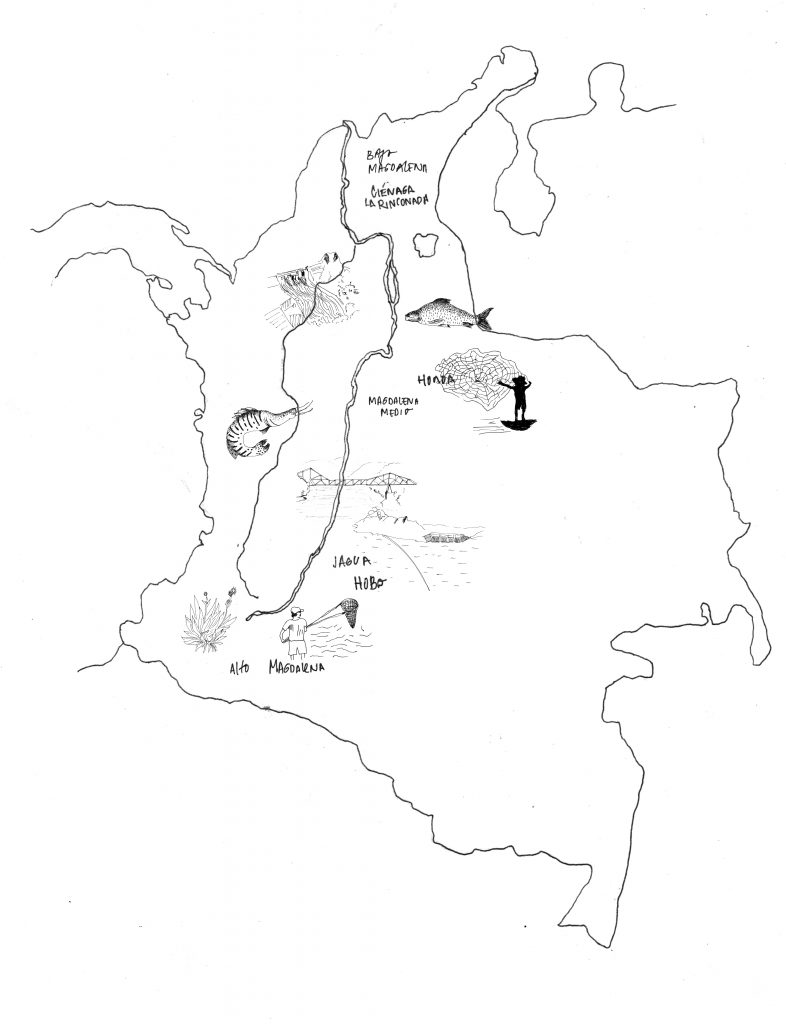

Life on the Magdalena River has included different dwellers and their changing entanglements. Throughout history, state interventions have neglected riverside communities as well as its animals, soils, and plants. Today, riverside people face changes in fish migration paths, floods, food shortages, and pollution, among others.

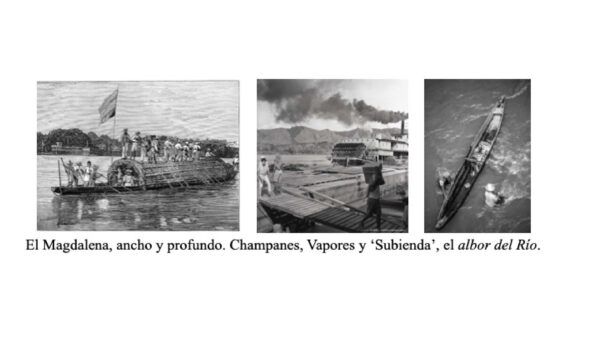

Over time, governments have prioritized activities different from those with long histories among riverside communities, like fishing. In the seventeenth century it was navigability projects; since the early twentieth century, it has been mainly hydroelectric dams and oil transportation. Other activities such as mining, which releases poisonous chemicals into the water, have had a tremendous impact.

But there’s hope for the future. Fishermen, local officials, and researchers devise mechanisms for addressing co-responsibility considering the unequal burdens generated by extractive companies, the state, and the fishing industry. A quest is underway to connect social and environmental justice.